Polio Place

A service of Post-Polio Health International

Charles Hudson Bynum

Born: November 11, 1905

Died: January 8, 1996

Major Contribution:

Charles Hudson Bynum was an African-American educator and civil rights campaigner who became the Director of Interracial Activities for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (March of Dimes) from 1944 to 1971. His path-breaking work of outreach to African-Americans with polio in the United States helped to ensure that black children and adults received proper treatment during polio epidemics and rehabilitative care.

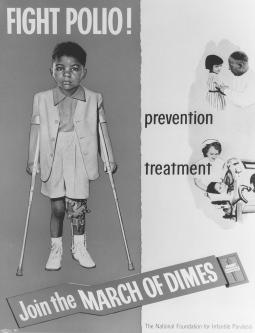

In his work for the March of Dimes, Mr. Bynum traveled widely through the U.S., but especially the segregated South, to facilitate the March of Dimes program of patient care in local communities for African-Americans with polio and to organize fund-raising efforts for physical rehabilitation and epidemic relief. He conceived and promoted the inclusion of African-American children in March of Dimes campaign posters to reach out to the black community most effectively.

Charles Bynum recognized that polio care was a civil rights issue and that the March of Dimes program of broad inclusiveness was a way not only to make polio care equal for all but also of normalizing race relations at a time of gross injustices and disparities in medical care caused by racial segregation.

Other Information:

Charles Bynum was born in Kinston, North Carolina. Prior to joining the March of Dimes he was a high school biology teacher, dean of Texas College in Tyler, Texas, and assistant to President Frederick Patterson of the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. Mr. Bynum was a leading advocate for the initial capitalization of the word Negro by the white press, especially in the South.

His work for the March of Dimes consisted of publicizing the fight against polio to the African-American community, recruiting black professional organizations such as the National Medical Association to join the fight, and ensuring that March of Dimes-sponsored polio care for blacks was applied equally and fairly. In the 1950s, Mr. Bynum conducted an annual fund-raising meeting at the Tuskegee Institute for black professionals and civic leaders. Tuskegee was a logical venue for the campaign as the March of Dimes had supported the institute in many ways, beginning with a grant for the construction of the first polio center for blacks at Tuskegee’s John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital. The Tuskegee Institute Infantile Paralysis Center admitted its first polio patient in 1941.

Charles Bynum insisted that equalizing polio care for blacks would be more effective if black children were included in March of Dimes posters. He stated in 1946: “Present practice is to use one child; to give significance to the appeal in Negro schools the poster should indicate that our services include the Negro child. … The poster should not be considered as a special appeal to a racial group. Recognition of a special population group is necessary not because of race but because it is impossible to demonstrate the validity of our pledge and the reliability of our staff without visual evidence.” Subsequently, the March of Dimes created a track of African-American children in its national publicity posters from 1947 to 1960. On the surface this seemed to accommodate segregation; in reality, these posters subverted segregation to ensure full participation and availability of services.

Mr. Bynum often experienced the indignities of segregated facilities himself in his travels to spread the appeal to join the March of Dimes. He continued his work through the 1960s to support African-Americans, to make sure blacks were represented fairly in March of Dimes chapters, and to integrate blacks fully in the mission to conquer polio. In 1963 he stated of the March of Dimes, “The image of ONE organization validating its service pledge was unique in the experience of the Negro public.”

February 24, 2011 / David Rose / March of Dimes Archives